BadSuccessor: Abusing dMSA to Escalate Privileges in Active Directory

Executive summary

Akamai researcher Yuval Gordon discovered a privilege escalation vulnerability in Windows Server 2025 that allows attackers to compromise any user in Active Directory (AD).

The attack exploits the delegated Managed Service Account (dMSA) feature that was introduced in Windows Server 2025, works with the default configuration, and is trivial to implement.

This issue likely affects most organizations that rely on AD. In 91% of the environments we examined, we found users outside the domain admins group that had the required permissions to perform this attack.

Although Microsoft states they plan to fix this issue in the future, a patch is not currently available. Therefore, organizations need to take other proactive measures to reduce their exposure to this attack. Microsoft has reviewed our findings and approved the publication of this information.

In this blog post, we provide full details of the attack, as well as detection and mitigation strategies.

Contents

Introduction

In Windows Server 2025, Microsoft introduced delegated Managed Service Accounts (dMSAs). A dMSA is a new type of service account in Active Directory (AD) that expands on the capabilities of group Managed Service Accounts (gMSAs). One key feature of dMSAs is the ability to migrate existing nonmanaged service accounts by seamlessly converting them into dMSAs.

While poking around the inner workings of AD’s dMSAs, we stumbled upon something interesting. At first glance, the migration mechanism looked like a clean and well-designed solution. But something about how it worked under the hood caught our attention.

As we dug deeper, we found a surprising escalation path: By abusing dMSAs, attackers can take over any principal in the domain. All an attacker needs to perform this attack is a benign permission on any organizational unit (OU) in the domain — a permission that often flies under the radar.

And the best part: The attack works by default — your domain doesn’t need to use dMSAs at all. As long as the feature exists, which it does in any domain with at least one Windows Server 2025 domain controller (DC), it becomes available.

This blog post explains how we discovered this, how the attack works, and what you can do to detect or prevent it.

What is a dMSA?

Before diving into the attacks, it’s important to understand what dMSAs actually are and how they’re supposed to work.

A dMSA is typically created to replace an existing legacy service account. To enable a seamless transition, a dMSA can “inherit” the permissions of the legacy account by performing a migration process. This migration flow tightly couples the dMSA to the superseded account; that is, the original account they’re meant to replace. That flow — and the permissions it grants along the way — is where things get interesting.

dMSA migration flow

The migration process of a dMSA can be triggered by calling the new Start-ADServiceAccountMigration cmdlet. Internally, it calls a new LDAP rootDSE operation named migrateADServiceAccount, which takes the following arguments:

- The Distinguished Name (DN) of the dMSA

- The DN of the superseded account

- A constant corresponding to StartMigration

The migration status of a dMSA is dictated by the msDS-DelegatedMSAState attribute — a new attribute that determines the current state of the dMSA. There is currently no official documentation on the msDS-DelegatedMSAState attribute, so the following table is based on our own behavioral analysis and experimentation.

Value |

Meaning |

0 |

Unknown (possibly disabled, but unconfirmed) |

1 |

Migration in progress |

2 |

Migration completed |

3 |

Standalone dMSA (no migration) |

msDS-DelegatedMSAState migration values and correlated meanings

Alongside this attribute, a few other notable attributes are used during the migration process.

On the dMSA object:

- msDS-GroupMSAMembership: Contains a list of principals that are authorized to use this dMSA

- msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink: DN of the superseded account

On the superseded account object:

- msDS-SupersededManagedAccountLink: DN of the “succeeding” dMSA

- msDS-SupersededServiceAccountState: Same meaning as msDS-DelegatedMSAState, specifying the original account migration state

Upon triggering a migration, the operation makes the following changes:

- Sets msDS-DelegatedMSAState to 1 (migration in progress)

- Updates the dMSA’s ntSecurityDescriptor to grant the superseded account:

- Read permissions

- Write access to the msDS-GroupMSAMembership attribute

- Sets the dMSA’s msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink to reference the superseded account

- Sets the superseded account’s msDS-SupersededManagedAccountLink to reference the dMSA

- Sets the superseded account’s msDS-SupersededServiceAccountState to 1

At this point, the dMSA is in a “migration in progress” state. It’s not fully functional yet but is now aware of which systems are still using the old service account.

Once the Complete-ADServiceAccountMigration command is issued, the following happens:

- The dMSA inherits key configurations such as SPNs, delegation settings, and other sensitive attributes from the superseded account

- The superseded account is disabled

- msDS-DelegatedMSAState and msDS-SupersededServiceAccountState are both set to 2 (migration completed)

The migration is complete and any service that relied on the superseded account will now use the dMSA for authentication.

dMSA authentication

Now that we understand the creation and migration process of dMSAs, it's time to focus on how authentication works, the changes introduced to support dMSAs, and how these changes make the migration process seamless.

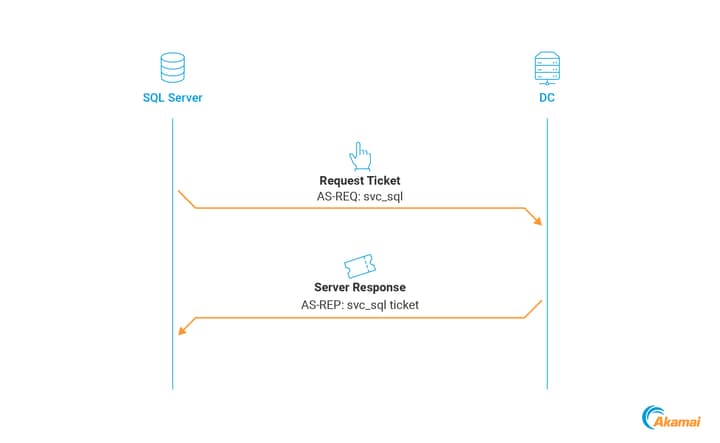

For easier understanding, let’s examine the svc_sql legacy service account, which is used to run a service on the SQL_SRV$ server. Whenever the service is required to access resources in the domain, normal authentication is performed using the svc_sql account (Figure 1).

Authentication during migration

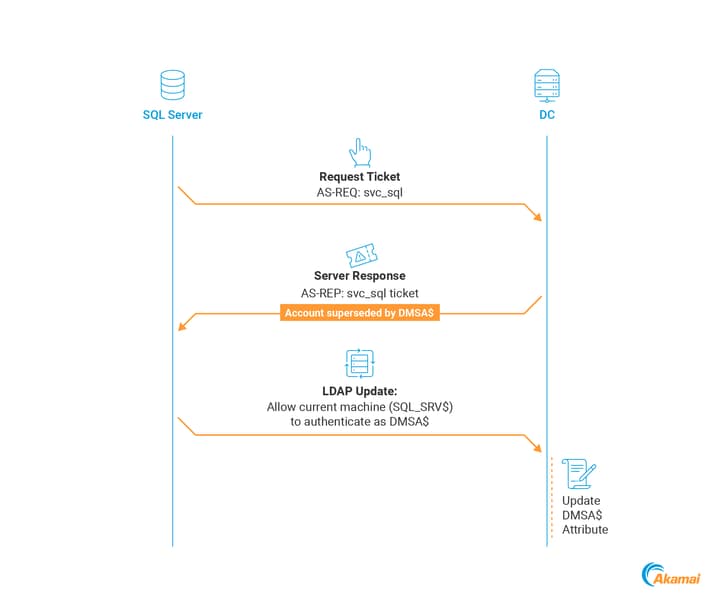

Now, we transition the service account to a new dMSA called DMSA$ and trigger a migration. During the migration period, when the service on SQL_SRV$ authenticates as svc_sql, the authentication flow is slightly modified.

The client sends an AS-REQ to authenticate as svc_sql

The Key Distribution Center (KDC) returns an AS-REP containing an additional field: KERB-SUPERSEDED-BY-USER (this field includes the name and realm of the new dMSA DMSA$)

If the host supports dMSAs (Windows Server 2025 or Windows 11 24H2) and has dMSA authentication enabled, it will:

Extract the DMSA$ name

Perform an LDAP query on DMSA$ to retrieve the following attributes:

msDS-GroupMSAMembership

distinguishedName

objectClass

Since the service is running on SQL_SRV$ as svc_sql, the authentication itself triggers an LDAP modify request from svc_sql, which adds SQL_SRV$ to the list of principals that are allowed to retrieve DMSA$’s password (Figure 2).

This is possible because, during the migration process, svc_sql was granted write access to the msDS-GroupMSAMembership attribute on the dMSA — a change that enables it to authorize its host machine to access the account's credentials.

This seamless permission grant ensures that by the time the migration is complete every machine that previously used svc_sql will be listed in the msDS-GroupMSAMembership attribute of DMSA$ — giving it the ability to authenticate as the dMSA.

Authentication after migration completion

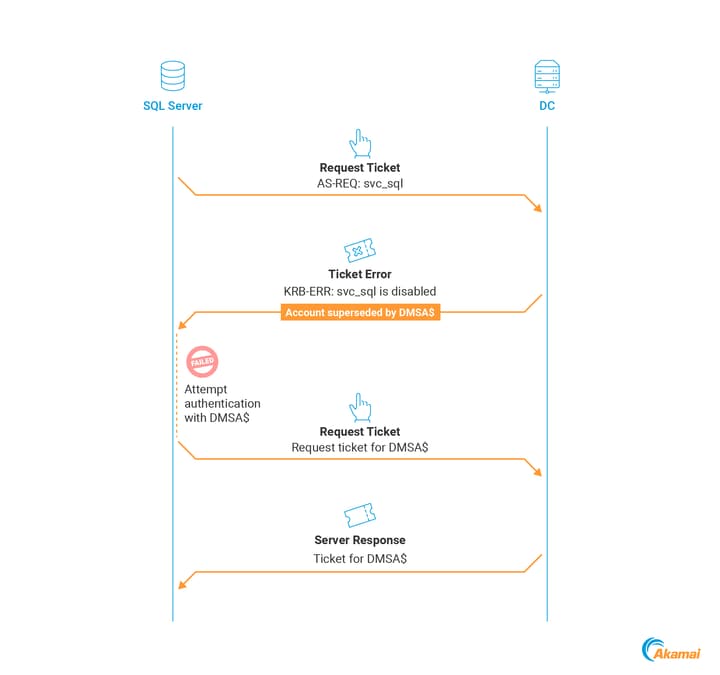

Once migration is finalized (via Complete-ADServiceAccountMigration), the behavior changes again.

When the client tries to authenticate as svc_sql by sending an AS-REQ, it no longer receives an AS-REP

Instead, the DC responds with a KRB-ERROR, indicating svc_sql is disabled

The KRB-ERROR will contain the KERB-SUPERSEDED-BY-USER field, allowing the client to recognize that svc_sql has been migrated and automatically retry authentication using DMSA$ (Figure 3).

SQL_SRV$ (and any other machine that previously relied on svc_sql) will now transparently switch to using DMSA$.

UnexPACted behavior

An interesting aspect of dMSA Kerberos authentication involves its Privilege Attribute Certificate (PAC).

When authenticating, Kerberos embeds a PAC into tickets — a structure that services use to determine a client’s access level. In a standard Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT), the PAC includes the SIDs of the users and of all the groups they are a part of.

However, when logging in with a dMSA, we observed something unexpected.

The PAC included not only the dMSAs SID, but also the SIDs of the superseded service account and of all its associated groups.

Abusing the dMSA migration process for privilege escalation

After migration, the KDC grants the dMSA all the permissions of the original (superseded) account.

From a design perspective, this makes sense. The goal is to provide a seamless migration experience in which the new account behaves just like the one it replaces — same SPNs, same delegations, same group memberships.

But from a security researcher’s perspective, this kind of behavior immediately stands out. When we saw a system that automatically copies privileges from one account to another, without requiring manual reconfiguration, we started asking questions: How does it decide which account to copy from? Can that be influenced? Can it be abused?

That line of questioning led us straight to a key discovery. This interesting behavior of PAC inheritance seems to be controlled by a single attribute: msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink.

The KDC relies on this attribute to determine who the dMSA is “replacing” — when a dMSA authenticates, the PAC is built based solely on this link.

It’s time to think like an attacker

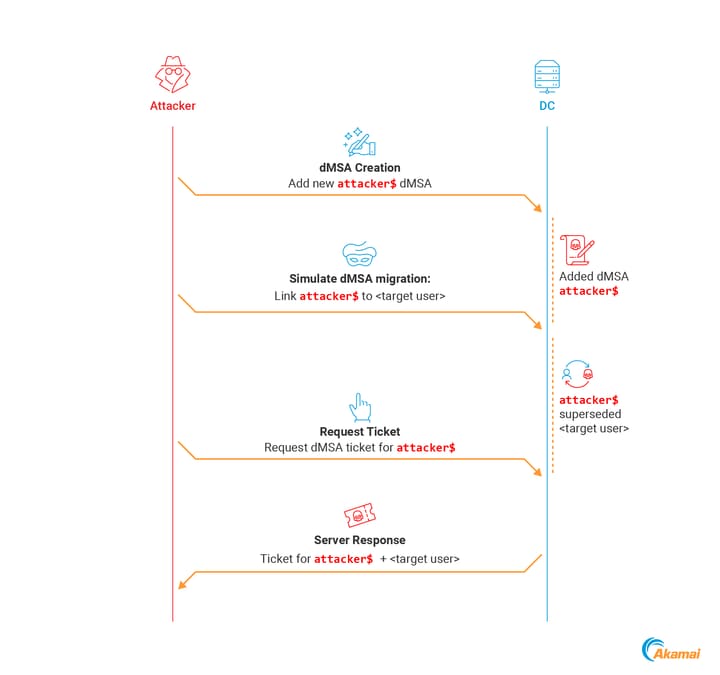

What does this look like from an attacker’s perspective? Let’s explore a possible attack scenario and see how far an attacker could get by using this feature.

Our first idea: Use a dMSA to create an account takeover primitive. If we assume that we have permissions over a user account, could we somehow “migrate” their permissions to a new dMSA to stealthily compromise them? That plan sounds solid! All we have to do is:

Create a dMSA

Start and complete migration between the target user and the dMSA using the migrateADServiceAccount rootDSE operation

Authenticate as the dMSA - Gain all permissions of the target user

The only problem: It doesn’t work.

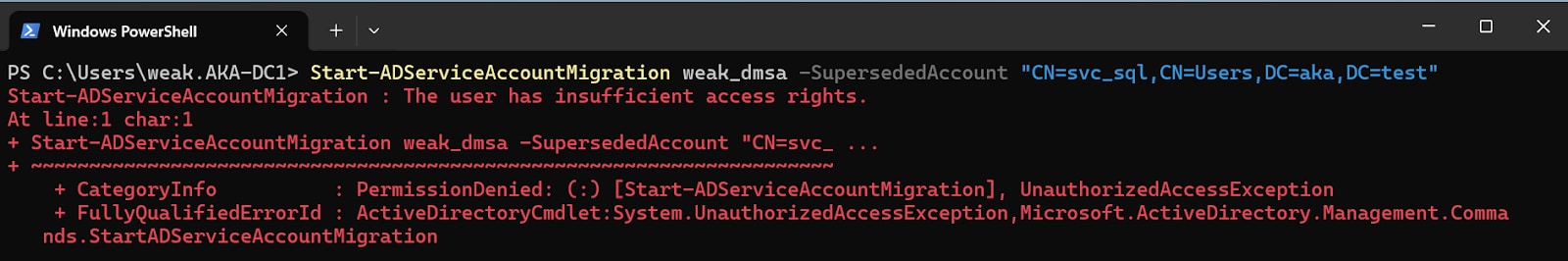

Even if we fully control both the dMSA and the superseded account, we can’t perform a migration, as the migrateADServiceAccount operation is restricted, as far as we know, to Domain Admins. Figure 4 shows an example of a failed attempt.

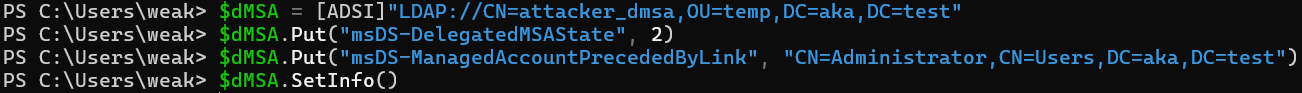

On to our second idea. Clearly, we need something complex, creative, and deeply technical. We need to explore undocumented behaviors, maybe even reverse engineer some part of the KDC … or we could just set two attributes.

Although we cannot directly perform a migration, we can very easily “simulate” one by simply setting the following attributes directly on the dMSA object.

- Write the target account’s DN to msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink

- Set msDS-DelegatedMSAState to value 2 (migration completed)

From this point forward, every time we authenticate as the dMSA, the KDC builds the PAC using the SIDs of the account linked to in the msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink attribute, effectively granting us the full permissions of the superseded account.

Introducing BadSuccessor

One interesting fact about this “simulated migration” technique, is that it doesn’t require any permissions over the superseded account. The only requirement is write permissions over the attributes of a dMSA. Any dMSA.

Once we’ve marked a dMSA as preceded by a user, the KDC automatically assumes a legitimate migration took place and happily grants our dMSA every single permission that the original user had, as though we are its rightful successor.

But, surely, this wouldn't work for high-privileged accounts, right? Well ...

Furthermore, this technique, which we dubbed “BadSuccessor,” works on any user, including Domain Admins (Figure 5). It allows any user who controls a dMSA object to control the entire domain. That’s all it takes. No actual migration. No verification. No oversight.

Exploiting dMSAs: From low privileges to domain domination

At this point, you may be thinking, “Well, I’m not using dMSAs in my environment, so this doesn’t affect me.” Think again.

One abuse scenario: An attacker gains control over an existing dMSA and uses this access to perform the BadSuccessor attack. But there is actually another scenario, which is likely going to be available to attackers much more often: An attacker creates a new dMSA.

When a user creates an object in AD, they have full permissions over all of its attributes. Therefore, if an attacker can create a new dMSA, they can compromise the entire domain.

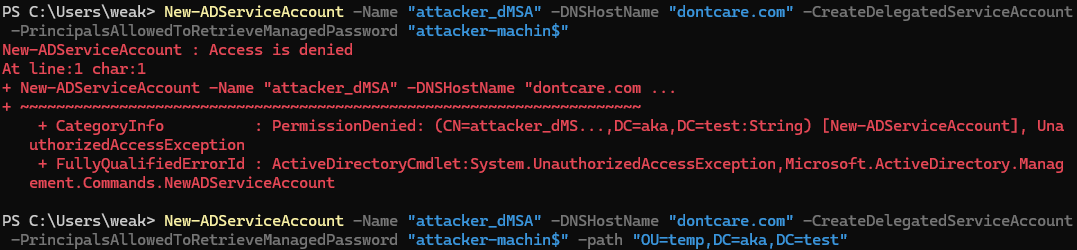

Normally, when a dMSA is created using the New-ADServiceAccount cmdlet, it is stored in the Managed Service Accounts container. Although it’s possible for users to be granted access to this container, only built-in privileged Active Directory groups have permissions over it by default. So it's not very likely that we would be able to write to this container.

dMSAs, however, are not restricted to the Managed Service Accounts container; they can be created in any normal OU, as well. Any user that has either the Create msDS-DelegatedManagedServiceAccount or Create all child objects rights on any OU can create a dMSA.

Creating the dMSA

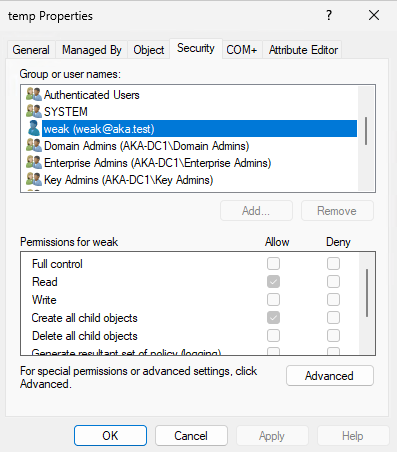

Allowing users to create objects in an OU is a fairly common configuration. As this ability is viewed as benign, it is not likely that users with this privilege will be monitored and hardened appropriately.

To create the dMSA, we start by locating an OU on which we have privileges. Luckily, someone has created an OU called “temp” in our example environment and gave our unprivileged user, “weak” permissions to create all child objects (Figure 6).

We can then use those permissions to create a dMSA using the New-ADServiceAccount cmdlet. As seen in Figure 7, while the unprivileged user cannot create a dMSA in the default MSA container, we can use the path argument to create the dMSA in the accessible OU.

We are now the happy owners of a newly created, unfunctional dMSA. As the Creator Owner, we can grant ourselves permission on the object, including write access on both the attributes we are going to use for this attack, which we can then modify in the following way:

msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink: Set this to any user or computer’s DN — Domain Controllers, members of Domain Admins, Protected Users, and (ironically) even accounts marked as "account is sensitive and cannot be delegated"

msDS-DelegatedMSAState: Set this to 2 to simulate a completed migration (Figure 8)

As we’ve mentioned, this attack seems to work on all accounts in AD. We were unable to find any configuration that would prevent an account from being used as a superseded target.

Grabbing a TGT for the dMSA

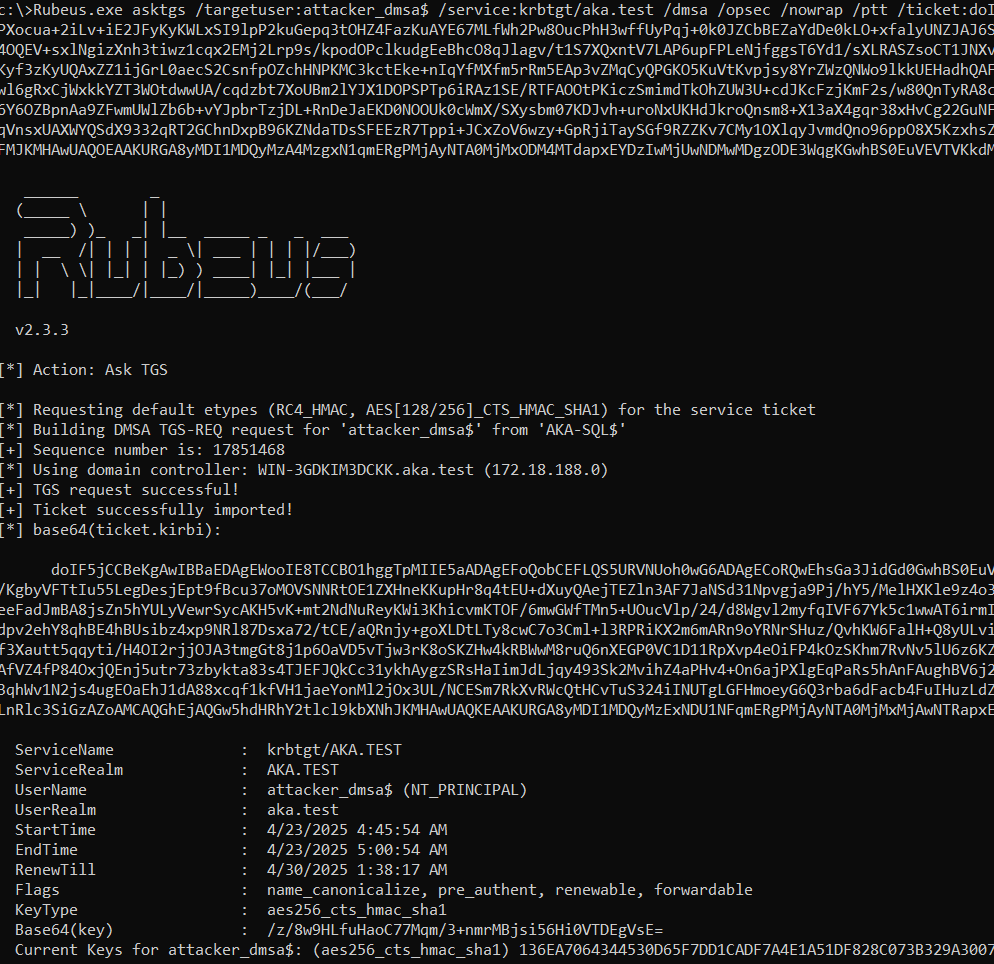

One way to authenticate with our dMSA would be to create a service and configure it to be executed with the dMSA account. This is possible, but not convenient. Luckily, thanks to a great pull request by Joe Dibley, Rubeus now supports dMSA authentication (Figure 9), meaning that we can use it to request a TGT for our dMSA:

Rubeus.exe asktgs /targetuser:attacker_dmsa$ /service:krbtgt/aka.test /dmsa /opsec /nowrap /ptt /ticket:<Machine TGT>

dMSA → Domain Admin

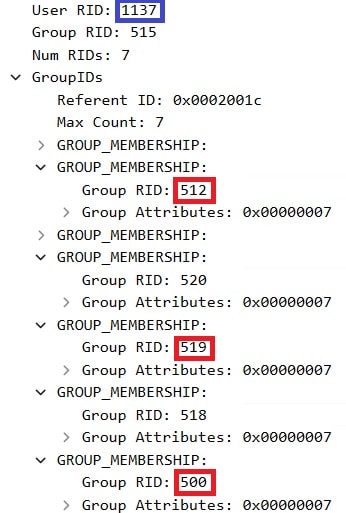

For this example, we targeted the built-in Administrator account. Using Wireshark, we inspected the PAC of the ticket we received for our dMSA (Figure 10), which included:

- RID of the dMSA (1137)

- RID of the superseded account (500 — Administrator)

- All the group memberships of the superseded account (512 — Domain Admins, 519 — Enterprise Admins)

This is all the Domain Controller needs to treat us as the legitimate heir. Remember: No group membership changes, no Domain Admins group touch, and no suspicious LDAP writes to the actual privileged account are needed.

With just two attribute changes, a humble new object is crowned the successor — and the KDC never questions the bloodline; if the link is there, the privileges are granted. We didn’t change a single group membership, didn’t elevate any existing account, and didn’t trip any traditional privilege escalation alerts.

Demo: End-to-end attack flow

Watch this video for a full demonstration of the attack in action.

Demonstration of abusing dMSA to escalate privileges in Active Directory

But wait, there's more — abusing dMSAs to compromise credentials

Getting a TGT for any user we want is cool, but we are greedy. What if we also wanted their credentials? Luckily, dMSA is here for us in this scenario, as well.

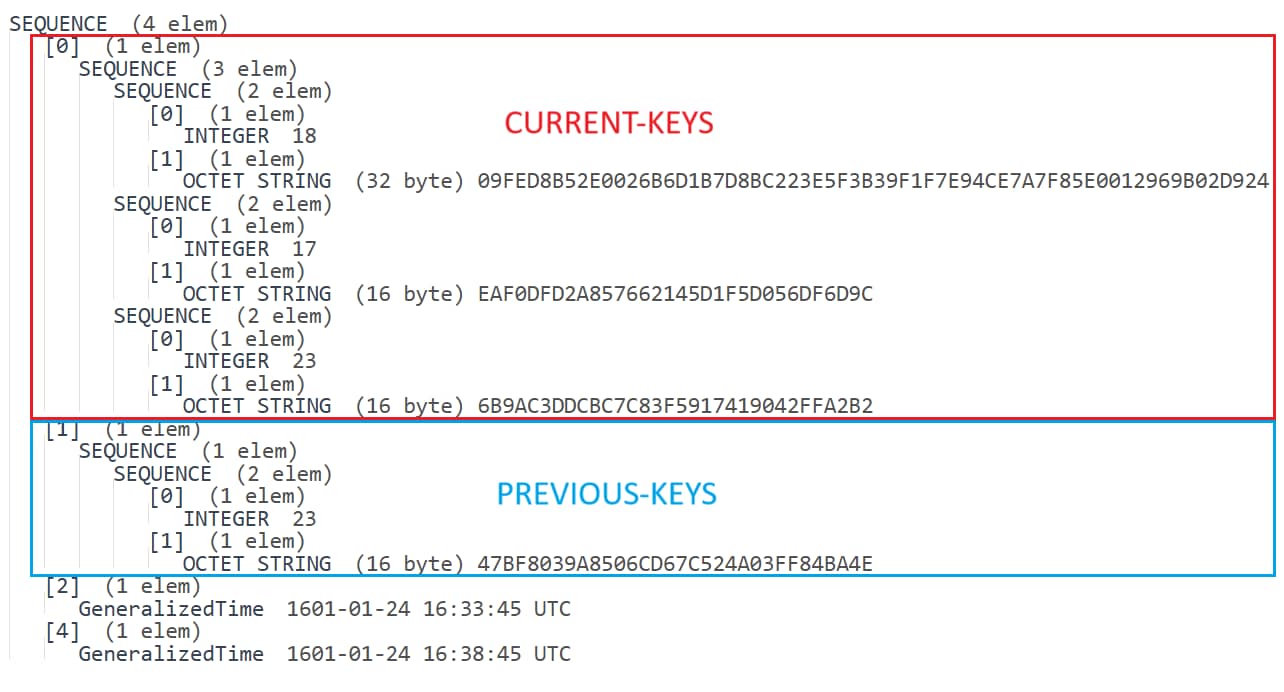

When you request a TGT for a dMSA, it comes with a new structure called KERB-DMSA-KEY-PACKAGE. This structure includes two fields: current-keys and previous-keys. According to MSDN, these are supposed to contain keys related to the current and previous password of the dMSA — and they do. But that's not the full story.

We were surprised to see that even when requesting a TGT for a freshly created dMSA, the previous-keys field wasn’t empty. Since it was just created, there should not be a “previous password.” We ignored this fact, until we realized something looked really familiar.

As shown in Figure 11, the second element in the structure held a single key with type 23 (RC4-HMAC). This encryption type is not salted, which means identical passwords generate identical keys, even across users.

And this particular key? Years of reusing the same password in lab environments finally paid off. We recognized it immediately. It was the key corresponding with Aa123456 — the password we used for our target account during the demo.

Let that sink in: The key for a separate account somehow ended up in the dMSA’s previous-keys structure.

Compromising keys at scale

So, what's happening here? And why?

The msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink doesn't just link the dMSA to the superseded account for permission purposes, it also lets the dMSA inherit its keys. This means that this attack can also be used to get the keys of any (or every) user and computer in the domain. We can use this key to authenticate with the account.

Although we have not analyzed the entire implementation, our theory is that this behavior exists to ensure seamless continuity during account migration for the end user’s benefit.

Let’s say we have a service running with a legacy service account. Accounts across the domain request tickets to this service, which are encrypted using the key of the legacy service account. Now, let’s assume we replace the legacy account with a dMSA, the migration completes, and the service account is replaced by the dMSA — but the dMSA doesn't have access to the old account’s key.

The result: When a client attempts to authenticate using their existing ticket, the server is not able to decrypt it using the new dMSA key, which makes all issued tickets unusable, even though they are not expired.

To prevent this kind of service disruption, the KDC includes the previous account’s keys in the new dMSA’s key package structure, treating them as if they were the dMSA’s own previous credentials and enabling it to decrypt “old” tickets.

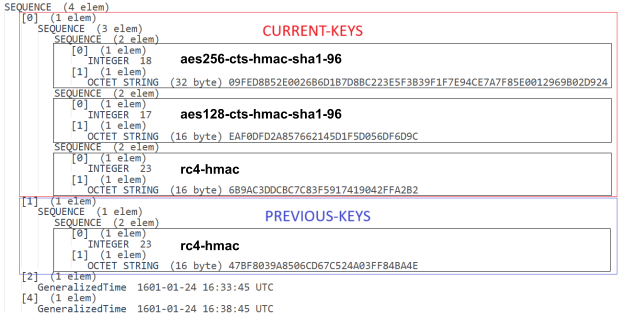

Once we understand this, another oddity starts to make sense. The current-keys field contains three elements, each consisting of an integer (representing the encryption type) and an octet string (the corresponding key). You can refer to this page to understand the encryption type values. In our case, the list includes keys for RC4-HMAC, AES256, and AES128. The previous-keys field, however, looks a bit different — it contains only one key, which corresponds to RC4-HMAC (Figure 12). Why does the previous-keys list contain only one key type, and why is it specifically RC4-HMAC?

The answer lies in the encryption types supported by the original (superseded) account. Service tickets are only encrypted using encryption types that the target service supports. As explained in Harmj0y’s excellent blog post, the msDS-SupportedEncryptionTypes attribute controls this behavior. If this attribute is not defined (default case for user accounts), the system defaults to RC4-HMAC only — hence the lone RC4-HMAC key in the previous-keys list.

In other words, the KDC gives the dMSA only the keys from the original account that would be necessary to decrypt service tickets issued prior to the migration. These are determined based on the encryption types supported by the original principal, which you can verify by inspecting its msDS-SupportedEncryptionTypes attribute.

Microsoft’s response

We reported these details to Microsoft via MSRC on April 1, 2025, and after reviewing our report and proof of concept, Microsoft acknowledged the issue and confirmed its validity. However, they assessed it as a Moderate severity vulnerability, and stated that it does not currently meet the threshold for immediate servicing.

According to Microsoft, successful exploitation requires the attacker to already have specific permissions on the dMSA object, which is indicative of elevated privileges. In response to the scenario of creating a new dMSA, Microsoft referenced KB5008383, which discusses the risks related to the CreateChild permission.

While we appreciate Microsoft’s response, we respectfully disagree with the severity assessment.

This vulnerability introduces a previously unknown and high-impact abuse path that makes it possible for any user with CreateChild permissions on an OU to compromise any user in the domain and gain similar power to the Replicating Directory Changes privilege used to perform DCSync attacks.

Furthermore, we've found no indication that current industry practices or tools flag CreateChild access — or, more specifically, CreateChild for dMSAs — as a critical concern. We believe this underlines both the stealth and severity of the issue.

Detection and mitigation

Detection

To detect potential abuse of this attack vector, organizations should focus on the following areas:

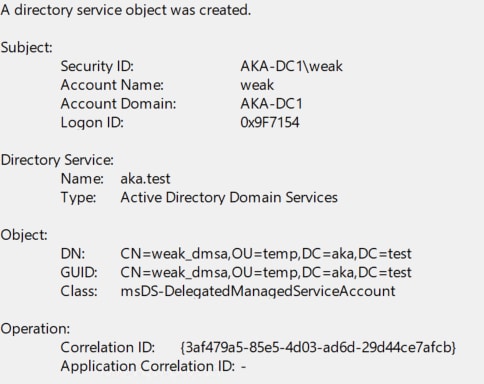

Audit dMSA creation — Configure a SACL to log creation of new msDS-DelegatedManagedServiceAccount objects (Event ID 5137; Figure 13). Pay special attention to accounts that are not typically responsible for service account creation.

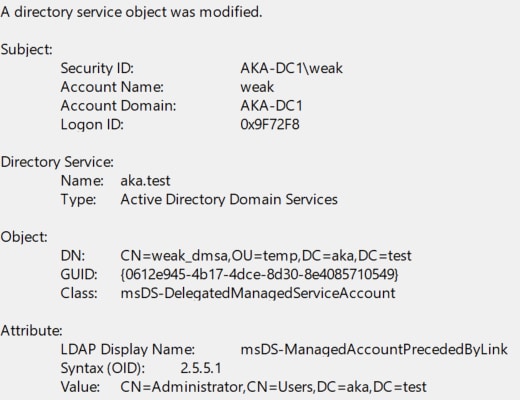

Monitor attribute modifications — Configure a SACL for modifications to the msDS-ManagedAccountPrecededByLink attribute (Event ID 5136; Figure 14). Changes to this attribute are a strong signal of an attempted or successful abuse.

Track dMSA authentication — When a TGT is generated for a dMSA and includes the KERB-DMSA-KEY-PACKAGE structure, the Domain Controller logs Event ID 2946 (Directory Service log).

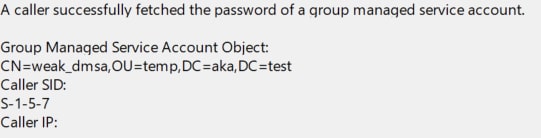

The Group Managed Service Account Object field (although this is a dMSA and not a gMSA) will show the DN of the dMSA being authenticated and the Caller SID field will appear as S-1-5-7 (Figure 15). Frequent or unexpected 2946 events involving unusual dMSAs should be investigated.

Review permissions — Pay close attention to permissions on OUs and containers. Excessively permissive delegations can open the door for this abuse.

Mitigation

Until a formal patch is released by Microsoft, defensive efforts should focus on limiting the ability to create dMSAs and tightening permissions wherever possible.

Defenders should identify all principals (users, groups, computers) with permissions to create dMSAs across the domain and limit that permission to trusted administrators only.

To assist with this, we have published a PowerShell script that:

- Enumerates all nondefault principals who can create dMSAs

- Lists the OUs in which each principal has this permission

Microsoft has informed us that their engineering teams are working on a patch, and we will update the mitigation guidance in this blog post once further technical details are available.

Conclusion

This research highlights how even narrowly scoped permissions, often assumed to be low risk, can have far-reaching consequences in Active Directory environments. Attackers are quite creative, and if recent technological advancements have taught us anything it’s that seemingly benign functions can have some deadly consequences in the wrong hands. dMSA was introduced as a modern solution for service account management, but its introduction also brought new complexity — and with it, new opportunities for abuse.

Organizations should treat the ability to create dMSAs or to control existing ones with the same level of scrutiny as other sensitive operations. Permissions to manage these objects should be tightly restricted, and changes to them should be monitored and audited regularly.

We hope this research sheds light on the risks that came along with Windows Server 2025 in general — and dMSAs, specifically — and helps defenders better understand and mitigate the potential impact of misconfigured permissions.